I got nauseated for the first time in VR today, and I’m still not sure if it was from losing my VR legs for a minute, or if it was because chat rooms in VR can get super weird. And there was a baby.

When Facebook bought Oculus in 2014 and declared social VR to be the future, there were many that were dismayed by the idea, as if the dark overlord had just revealed his plans to control, and therefore ruin, their VR dreams. Mark Zuckerberg has reiterated on numerous occasions that “VR is going to be the most social platform,” and though I agree with him, it is unfathomable to me that people think that he came up with this idea, or will be in any way able to dominate the space.

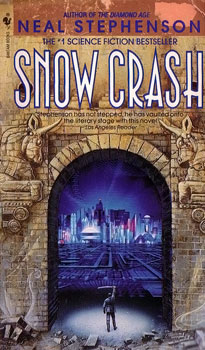

The dream of social VR really goes back to Snow Crash (Stephenson, 1992), where the “Metaverse,” a virtual alternate reality that is reached by using one’s computer to interact with others using your avatar, is laid out in great world-building detail. I know that Gibson started pulling at a similar thread in Neuromancer (1984), but I don’t think he fully realized the extent to which social interaction would act as VR’s raison d’être. Like many others, I consumed the book within a few years of its release not quite grokking that VR would someday soon be realized.

The dream resurfaced in 2003 when Second Life launched, a massively multiplayer online, and ultimately clunky and disappointing, video game aimed at providing a user-created, persistent virtual world. I was fascinated by the idea behind it, and spent far too many hours suspending disbelief in the primitive graphics and low frame rates.

Though the technical challenges of relatively low internet speeds and the game’s way of delivering graphics (the server would generate the image and send the image to the user) proved to be too much for the success of the game, it was at least a successful step in the direction of the dream of the social virtual world. Yes, there was a lot of weird stuff in Second Life too, from sex dungeons to griefers, but it still felt enough like a video game – 2d screen, clunky controls – that it never really impacted me in a negative way.

Fast forward to today, when technology is finally starting to catch up with the VR dreams of 25 years ago, there are multiple social VR platforms, and I entered one with no reservations. After a couple of false starts getting things set up, I finally found myself in a room with about 15 other floating avatars hanging around a huge screen showing YouTube videos. There was an interface where anyone can search for and add videos to the list, vote on which one they want to see next, and vote to skip the one currently playing.

I was immediately hit with a wave of anxiety, which is weird, since I’ve been comfortable with every other VR game I own and have played for a couple of months, and spent countless hours in my 20’s playing social games on 2d screens. This time it felt more real, more immediate. More weird. A video of someone in a wheel chair sloppily eating a chili dog was quickly followed by real footage of Hitler giving a speech, and one of the avatars immediately stood in front of the screen and started shooting ‘applause’ emoji out of his head. After retreating to the back of the room and asking a few questions about how the video interface worked, and about halfway through the subsequent borderline softcore porn Nicki Minaj video, the baby appeared.

Well, child, I guess. Their avatar was about half as tall as the other avatars, which makes sense in retrospect, since the headsets are tracked in space, and the kid was actually closer to the ground in real life; it was actually a toddler on the other end, donning a VR headseat and fully engrossed. The short avatar was waving their Vive controllers at other people, saying “hi!” and mumbling lots of nonsense, as toddlers tend to do. I was both hit with a jolt of cuteness because, well, toddler mumbling is cute, and a wave of dread, since there are so many potential ramifications of a tiny child wandering around unsupervised in a VR social space. When a death metal video came on the screen and someone said suggestively next to the child, “this song makes me want to kill my parents,” a couple of us went in search of a mod to try and kick the pint-sized orphan out for their own good.

Social VR has a lot of potential – the immediacy of VR can convey emotion in highly concentrated doses – but much like Reddit or other social platforms, it will only truly shine when heavily moderated, and therefore is perceived as safe. A VR version of 4chan’s /b would be truly terrifying. Call me old and stodgy, but if you’ve never felt the impact of social VR then you don’t yet know how much it starts to feel like real life, and we have established social and legal rules in real life.

I’m not saying that we should try to rule the VR social space with an iron fist (we know that never works online), but that if we are going to have little kids running around, probably unable to distinguish between real worlds and virtual worlds, then we need to start putting some serious though into how all this is going to work. Because the dream is finally here, and everyone should pay attention.

As I ripped off my headset last night and tried to recover from my persistent feeling of sweaty nausea, I questioned whether what I had experienced was good or not. I think, just like life, social VR is both good and bad, and extremely weird, and that alone is enough evidence to show that virtual worlds are finally here.